Contents

Worried about how your child’s GCSEs will be marked? Or wondering what a grade 6 actually means in real terms?

The current 9–1 grading system replaced the old A*–G scale several years ago, but it can still cause confusion, especially if you're more familiar with the old system.

Whether you're a student trying to understand your targets or a parent trying to support revision, it's important to know what each grade means and how they’re awarded.

In this guide, we’ll explain:

What the 9–1 grading system is and why it was introduced

How grades compare to the old A*–G scale

How exam boards decide grade boundaries

What counts as a 'pass'

How GCSE grading affects future pathways

What is the 9–1 GCSE grading system?

The 9–1 system was introduced by the Department for Education as part of wider GCSE reforms in England. It was first used for English and maths GCSEs in 2017 and now applies to almost all GCSE subjects across all major exam boards (AQA, Edexcel, OCR, WJEC Eduqas, and CCEA).

Instead of letter grades, students receive a number between 9 (the highest) and 1 (the lowest). Grade 9 is designed to recognise exceptional performance and sits above the old A*.

The system was designed to:

Better differentiate between the highest achieving students

Create a more rigorous, linear style of assessment

Make it easier to distinguish between reformed and legacy GCSEs

How do the new grades compare to the old A*–G scale?

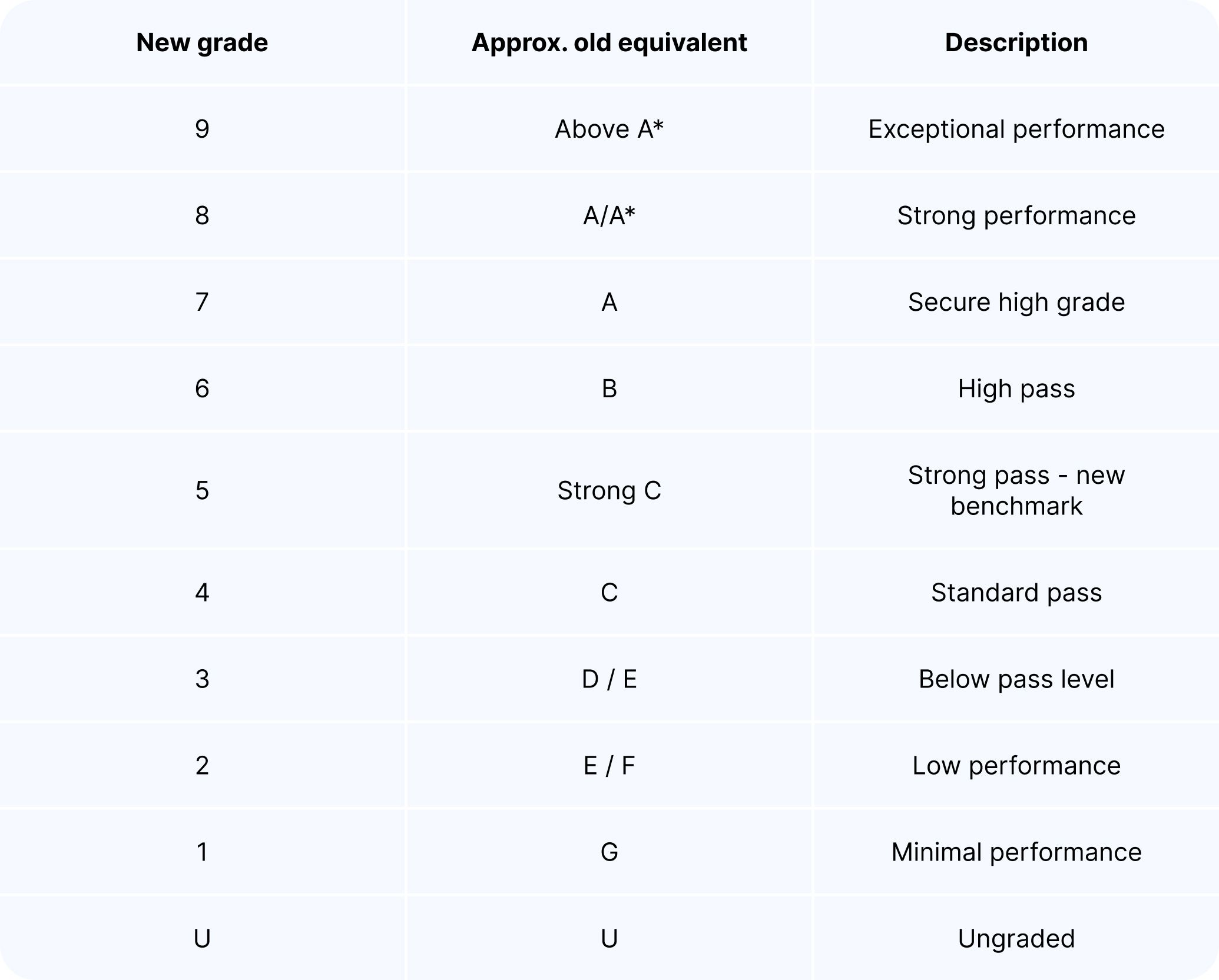

While the 9–1 scale doesn't map exactly onto A*–G, there are general comparisons that help make sense of it.

What is a pass at GCSE?

There are two main types of pass in the current system:

Standard pass: Grade 4. This is the minimum grade that is generally accepted as a pass by employers and further education providers.

Strong pass: Grade 5. This is a higher benchmark that is used in school performance tables and by some sixth forms or colleges as an entry requirement.

A grade 3 or below is considered a fail. Students who do not achieve at least a grade 4 in English and maths are usually required to resit those subjects.

For students taking Combined Science, you need to get a 4-4 for a standard pass. Find out more in our guides to Combined Science for AQA, Edexcel and OCR.

Free revision timetable template & more

Less stress, more success! Get your free revision timetable templates and guide to effective revision today. Because great revision starts with a solid plan.

How are GCSEs marked and graded?

After students sit their exams in the summer, each paper is marked by trained examiners from the relevant exam board. Marks are then totalled for each paper, and grade boundaries are applied to convert raw marks into final grades.

Grade boundaries can change each year. They’re set based on a combination of:

Statistical evidence (to ensure year-on-year fairness)

Expert judgement (on question difficulty)

Performance data from a representative sample of students

This means that while papers might vary slightly in difficulty from year to year, the grading process is designed to keep outcomes fair and consistent.

Why were GCSE grades changed to numbers?

The move to numerical grades was part of a wider reform of GCSEs in England to make qualifications more rigorous and meaningful. The changes aimed to:

Reflect higher expectations of student knowledge and skills

Reduce grade inflation seen under the A*–G system

Give universities and employers better information about student ability

In particular, the top end of the scale was stretched to allow greater differentiation. For example, under the old system, A and A* covered a wide range of ability. Now, grades 7, 8 and 9 separate those students into clearer categories.

What impact do GCSE grades have?

GCSE grades can influence a range of next steps, including:

Sixth form or college entry: Many require at least five GCSEs at grade 4 or above, including English and maths.

A level subject choices: Some subjects require a grade 6 or above in the same subject at GCSE.

University admissions: Competitive universities look at GCSEs in addition to A levels.

Apprenticeships: Employers often expect minimum passes in English and maths.

Future careers: GCSEs can be important indicators of academic strength, especially in core subjects.

Summary

The 9–1 GCSE grading system may look unfamiliar, but it plays a crucial role in helping students, schools and employers measure academic progress more clearly. Grade 9 rewards the very top performers, while grade 4 remains the baseline for a standard pass.

Understanding how the system works can help students set clear goals, track progress and feel more confident going into exam season.

Don’t miss Atom’s GCSE giveaway!

Six months. Six epic prizes. Six chances to make the GCSE season unforgettable.

We’re launching Atom for GCSE prep in 2026, and to celebrate, over the next six months, we’re giving away thousands of pounds worth of prizes to help your child level up their GCSE revision.

Here’s a taste of what’s up for grabs:

The latest Apple tech, including an iPad Air, Vision Pro and more

Festival tickets for Boardmasters and Reading 2026

Europe interrail passes and £1,000 spending money

…and that’s just a few of the amazing prizes available.

Our first two winners have already taken home incredible prizes! Find out who they are and what they won in our latest giveaway update and keep an eye out for news of our November winner.

It’s free to join. UK only. Full T&Cs apply.

Contents