Dyslexia deciphered: what parents need to know

There’s a lot of information online about dyslexia but much of it can be confusing and even contradictory. Here, Zara clarifies some of the debates and cuts through the jargon of dyslexia to help you understand more.

Zara Carey is a maths teacher and Special Educational Needs Coordinator. She consults and writes on inclusion, fair access to the curriculum, and supporting learners with additional needs to reach their potential.

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a learning disability that commonly affects reading and spelling. The skills used for language accuracy and fluency are impacted. People with dyslexia can have trouble processing words which results in reading difficulties and trouble spelling.

Dyslexia is a non-medical diagnosis and is assessed through examining a child’s phonological processing. For your child to be identified as having dyslexia, they need to have a persistent literacy difficulty which does not improve, despite well-founded literacy interventions.

A brief history

The term ‘dyslexia’ was coined by Rudolf Berlin in 1887. It means ‘difficulty’ with ‘words’ which is perhaps the most helpful definition for us to use today. Since the inception of the term, dyslexia has gone through many iterations.

In the early 20th century it was widely thought that reading difficulties were caused by visual processing problems. This was partly because the dominant method for teaching reading at that time was ‘whole word’ reading or sight reading, where a child learns to recognise whole words. If a child found it difficult to recall the word when looking at the group of letters, it was assumed they were struggling to visually identify the shapes and symbols.

Teaching methods for reading

Sight reading

Memorising whole words by sight so they can be recognised when reading in the future.

Phonics

Learning the sounds associated with each letter in the alphabet, plus letter blends and digraphs. Words are sounded out.

During the 20th century the reading instruction pendulum swung between sight reading and phonics with avid proponents on either side. More recently phonics teaching has become widespread. If your child is educated in the UK it’s likely they will begin learning a detailed phonics programme in reception class.

With phonics now the dominant teaching method, it has become clear that the barrier to reading for many people is their difficulty with isolating speech sounds (‘phonemes’).

Recent debates and definitions

In recent years the definition of dyslexia has been hotly debated. It used to be argued that dyslexic people have higher than average ‘intelligence’ but a specific difficulty with learning to read. More recent scientific investigation has led to dyslexia being given a more inclusive definition with no bearing on a person’s level of ‘intelligence’. It is currently understood as anyone who has difficulty acquiring the skills needed for fluent reading.

Whether your child is having difficulty with learning to read only, or whether this difficulty is one among a few you have noticed, it is worth considering whether they might have dyslexic-type needs.

What skills are needed for fluent reading?

As a parent you’ll know that there a multitude of skills needed for strong reading. Factors include vocabulary and contextualising, but let’s focus on the skills needed for accurate word decoding, as this is where your child might struggle the most if they have dyslexia.

Accurate reading requires good phonological processing. While children can memorise how common and familiar words look (sight reading), when they encounter unfamiliar and longer, more complex words, they will need to use phonics, or phonological processing, to sound out the new word.

Phonological processing involves three separate skills:

Phonological awareness

Understanding the sound structure of your own language (e.g. knowing the exact sound differences between cat, sat and mat).

Phonological memory

Translating between symbols and sounds for temporary storage in short-term memory (e.g. understanding instructions).

Verbal processing speed/rapid naming

How quickly, when looking at symbols e.g. letters and numbers, you can remember their sounds (e.g. spelling aloud, reading out a phone number).

The explicit teaching of phonics, which is compulsory in all UK primary schools that follow the national curriculum, can help to close gaps in a child’s phonological awareness. But some children will still find it hard to discriminate individual sounds when listening to a word.

If your child has poor phonological memory or verbal processing speed these will be harder to improve through explicit teaching. It is more effective for their teacher or teaching assistants to make adjustments. It is for this reason that children who encounter these difficulties are identified as having dyslexic-type needs and are eligible for support in their learning.

What are the signs of being dyslexic?

If you think your child may have dyslexia, here are some questions you can ask yourself and things to look out for, as well as of course gathering insights from their class teacher and any other educators who work with them.

Persistent difficulties

Reading is a complex and difficult skill so understandably, it takes a long time for children to master it. From Early Years (age 3) right through to the end of Key Stage 1 (age 7) your child’s progress with reading will probably not be linear. They may seem to have massive leaps in their reading skills, only to have ‘forgotten’ some of the letters and words soon after.

They may also have phases where they are not at all interested in reading or seem to be actively avoiding it. Don’t worry if this happens – it’s likely that their brain is prioritising another area of development at these times, such as spoken communication or movement.

That said, if all reading progress is temporary, or your child is not moving on from one skill to a more complex skill after many months of practice, they may have a dyslexic-type difficulty which is halting their progress.

Phonological awareness

Phonemes

Thinking back to when your child first began to read, did they have a prolonged difficulty memorising the letter sounds? Children experiencing the early traits of dyslexia may look blank or confused when asked to recite the sound of a certain letter, despite having practised that sound for several months.

They may also do lots of guessing which can sometimes be correct but sometimes be completely random. For example, if they guess the sound ‘o’ when looking at a ‘d’ this is reasonable because the ‘o’ shape is contained within the ‘d’ letter. However, if the sounds they make are completely unrelated to the letter, this could suggest they’re having trouble connecting the letter and the sound.

Blending

Other children with dyslexic-type needs may be very good at ‘memorising’ the letter sounds. It may be that your child knows the phonetic sound of every letter in the alphabet, but when it comes to stringing the sounds together they show great difficulty.

Can your child consistently blend some sounds to make more complex sounds? They may not know all the blends perfectly yet but if your child is in Key Stage 2 (ages 7–11) you should notice that there are many blended sounds they can pronounce each time with ease. For example:

- Do they always get ‘gr’ right?

- Do they always say ‘ow’ when they see ‘o’ and ‘u’ together?

The second example is an interesting one, because of course there are many exceptions to the rule that ‘ou’ is pronounced ‘ow’. However, if your child is usually able to blend sounds, tricky exceptions aside, they are showing good phonological awareness.

It’s worth noting that English is not an easy language to learn to read.

In Italian, for example, there are seven vowel sounds which are ‘pure’, meaning they do not change when combined with other letters. In English we have 15 vowel sounds, which change according to what letters they appear next to. If the emphasis of the word does not fall on the vowel in English, the vowel often takes on a neutral, ‘uh’ sound (known as a ‘schwa’) rather than retaining its pure vowel sound.

Learning English is not an easy journey for many children. Some children with dyslexia are given Italian or Spanish lessons to help them build confidence with language learning and gain experience learning a language that is more ‘logical’ and straightforward.

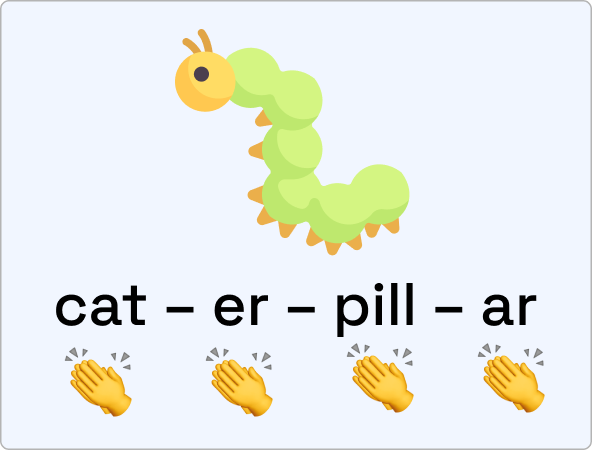

Segmentation

Is your child able to rhyme easily? Rhyming shows the ability to take one part of a word, remove it and replace it with ease. As well as being able to blend sounds, your child needs to be able to segment what they hear or read from sentences into words, from words into syllables and from syllables into sounds. This is crucial in their ability to process auditory information (where it is not obvious where one word ends and another word begins) but also in their ability to spell.

This is why dyslexia is often associated with difficulty spelling – a child with poor phonological awareness may find it very hard to divide up the word they are hearing into easily spellable chunks. Good ways of investigating your child’s ability to segment are clapping words in a sentence and clapping syllables in a word.

Phonological memory

Can your child repeat words, phrases and lyrics back to you? If your child has poor verbal memory they may find it difficult to store things they have just heard or read. They may struggle to remember the words to rhymes and songs. You’ll notice that when they are reading, they may be able to read each word in the sentence but will not find it easy to keep the series of words in mind and follow the meaning of the sentence.

Asking your child simple questions about what they have just read will help you see whether they are struggling with comprehension. Using pictures for context when reading is an important skill in Early Years and Key Stage 1, but during Key Stage 2, children should begin to understand the meaning of an age-appropriate text without a picture to support them. If you notice your child relies on pictures to help them answer comprehension questions, this may be because they are finding it difficult to store the series of words in their head.

Children who struggle with verbal memory also find it hard to follow instructions, stay organised and keep good timing. In a dyslexic child, these difficulties are related to their language comprehension. So if you ask your child to go upstairs, clean their teeth and bring down their socks you may find that they often forget one of the things you have asked them to do.

Of course, many young children are forgetful. This would only suggest a possible language difficulty if it happens regularly and doesn’t improve despite you trying tactics to help them remember, e.g. asking them to count how many things they need to do upstairs or asking them to repeat the instructions back to you.

Verbal processing speed

Does your child have difficulty recalling things quickly, such as times tables, months of the year, or spelling aloud? They may have a lower verbal processing speed, meaning that it takes them a while to retrieve things from their permanent memory.

Other possible indicators of this difficulty are that a child may have a small pool of memorised words. This may mean they prefer to write stories about things they know well, and they may be reluctant to experiment with new vocabulary both when writing and talking.

As we have seen, learning to read is difficult – especially in English. It depends on a huge range of micro-skills which your child is developing at the same time as speaking skills, social skills, emotional skills, physical skills and cognitive problem solving. If your child experiences any of the difficulties mentioned above for a short period this shouldn’t be a reason to suspect dyslexia.

However, if the difficulties persist, at school and at home, despite teachers and parents trying a variety of techniques to help, then it is worth speaking to your child’s class teacher and Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO) to see if there may be an underlying difficulty getting in the way of their progress.

The next article in this series talks about steps to take if you think your child may have dyslexia, from supporting your child’s learning at home to getting support in the classroom.

Interested in how technology can help children with special educational needs and disabilities? Learn more here.

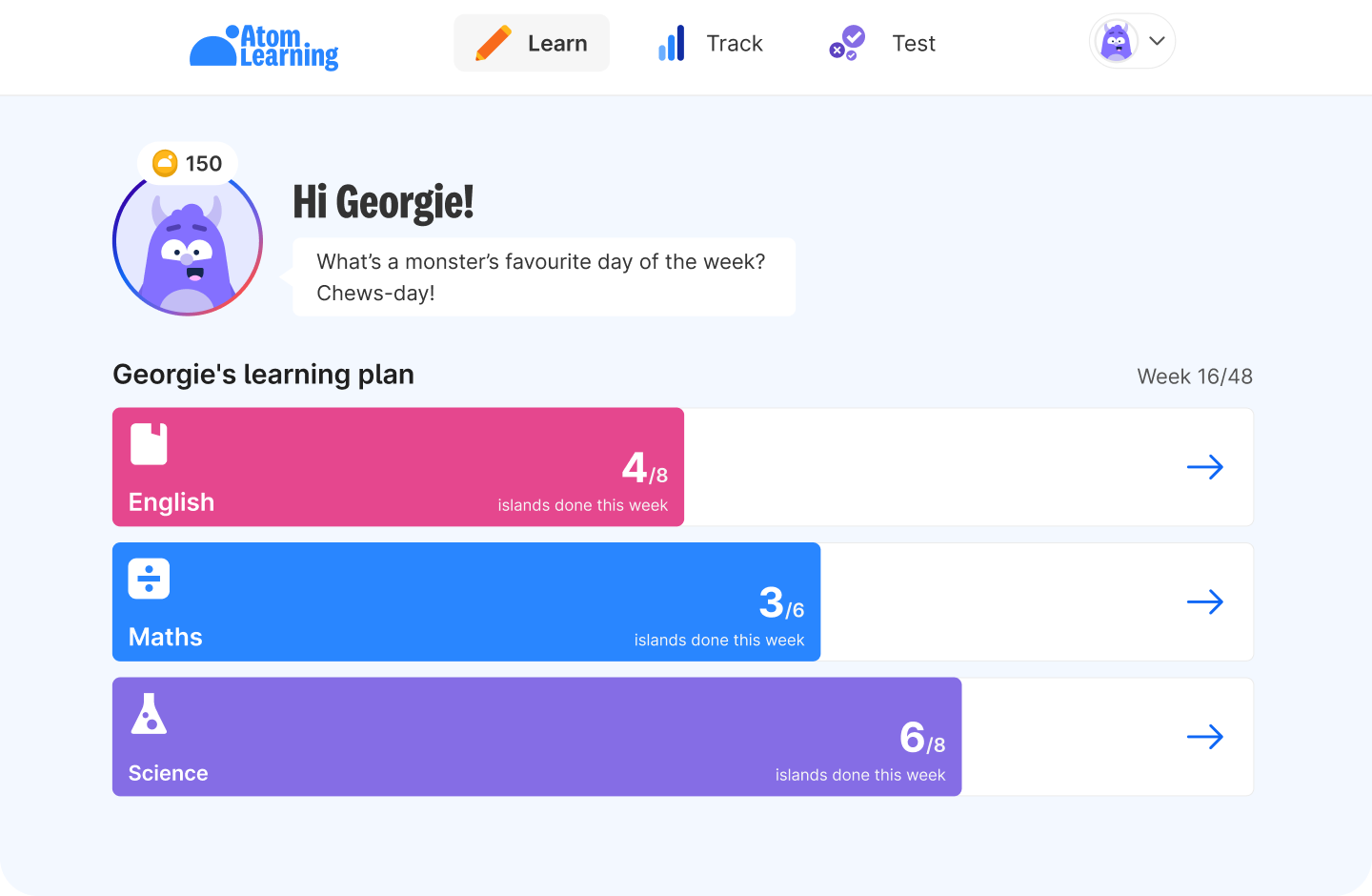

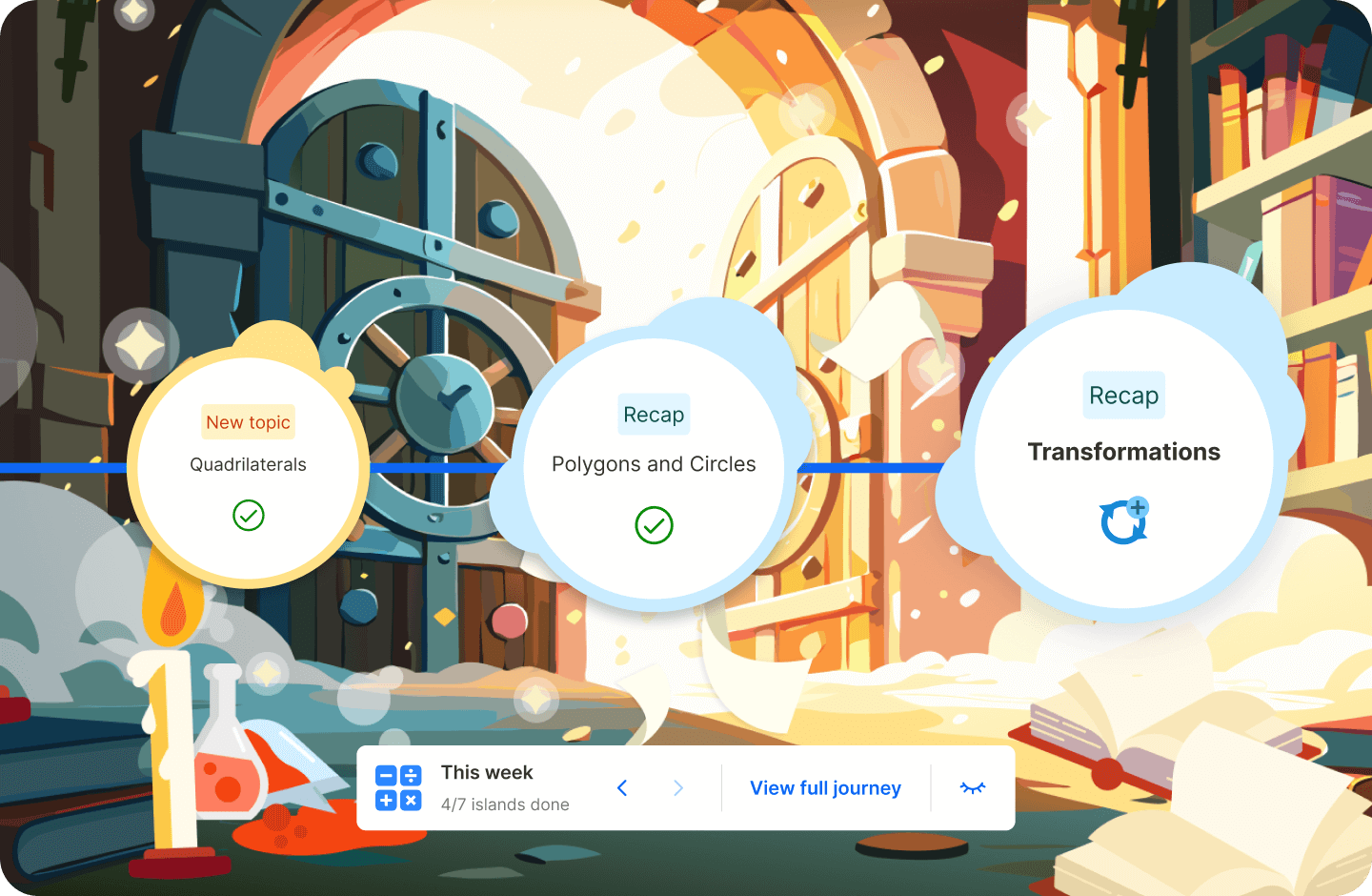

Build strong English, maths and science skills.

Want to support what your child is learning at school, or help them stretch beyond it? Atom gives them the right blend of challenge and support. Help them strengthen foundations, deepen understanding, and grow confident in the subjects that matter most for Key Stage 2 and beyond.

- Follow personalised weekly learning plans that adapt to your child’s level and keep them progressing in English, maths and science.

- Learn through interactive lessons that stretch their thinking and reinforce key skills.

- Track progress topic by topic. See their strengths and pinpoint where they need to improve.

Start your free trial and help your child make real school progress today.