Supporting your child with dyslexia

You've done some research into dyslexia and think your child may be showing some traits. What next? Zara explains how to seek support and shares top tips to help at home.

Zara Carey is a maths teacher and Special Educational Needs Coordinator. She consults and writes on inclusion, fair access to the curriculum, and supporting learners with additional needs to reach their potential.

Communicate with school

If you've noticed your child has dyslexic-type difficulties, the first step is to organise a meeting or phone call with their class teacher. Their teacher and any learning assistants see your child learn all day every day, so they'll have a great insight into whether the difficulties persist at school and how they affect your child’s learning. It may be wise to ask your child’s teacher to monitor them for a short period and get back to you.

If the class teacher agrees that your child is experiencing barriers to learning how to read and write, you should jointly contact the Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO) at your child’s school so that they can do some further observations if necessary, and make recommendations about support. If your child has many subject teachers, it's best to contact their form tutor and the SENCO who can gather information from their different subject teachers.

Boost reading and writing at home

Before and during the process of communicating with school, you can boost your child’s reading and writing, letter and word learning at home. Here are my top tips:

Foster a love of reading

Make reading appealing by reading yourself in front of your child and being enthusiastic about reading time: "I’m going to go and relax and read my book" and "Wow my book is so good, I can’t stop reading it!"

Read with your child every night at bed time and take turns reading paragraphs or pages. This models good reading to them but will also likely encourage them to try and imitate the confident flow of your reading aloud.

Help your child to make or buy a nice notebook where they can keep a glossary of new words they come across and what they mean.

A good way to hook your child onto a book is to buy or borrow books that are related to some of their favourite characters, animals or themes. If they love a particular television programme you can get the accompanying books, or if they have a particular fascination with the sea or safari animals you can choose books along those themes.

If your child has siblings, cousins or close friends who love reading you could initiate discussions about what their favourite books, characters or stories are and why they like them.

Download free Key Stage 2 reading lists

Find your child’s next great read. Atom’s free KS2 reading lists include carefully chosen books to help children aged 7–11 build comprehension, expand vocabulary and develop a genuine love of reading. Perfect for reading at home or alongside school learning.

Encourage a habit of writing

Many students I come across do no writing at home. Those with learning difficulties can begin to see writing as something difficult that they do at school and that they find harder than their peers. While many parents are excellent at reading with their children, many do not think about writing beyond birthday cards.

Diaries

Diary writing is an invaluable way to improve your child’s writing. As they recount events, such as what they got up to at the weekend, you can encourage them to expand on things by asking them to describe what things looked like, what they could hear, how they felt and so on. You can offer one or two good descriptive examples each time they write so they are reminded of what good, detailed writing looks and sounds like.

Diary writing is particularly good for dyslexic learners as they can struggle with sequencing (recalling and retelling events in a meaningful order). If your child is someone who struggles with sequencing you can ask them to draw a quick comic before they start writing, or to list what happened in bullet points before writing full sentences. Children are never too young to learn how to plan their writing – it will prove a very helpful skill for their whole school experience.

Letters

Writing letters to friends and family is a fun way to get children writing. Many kids enjoy the feedback and praise they get from their family when the letter is received, and the novelty of getting letters addressed to them in the post.

Reviews

Children love to be experts so if you get them in the habit of expertly reviewing films, books, TV shows, toys (anything really!) then you may be on to a winner for getting them to write often and without hesitation or trepidation.

News reports

Some of the best literacy resources for children are based around the news. Newsround, The Week Junior and The Day are incredible fonts of accessible, intelligent writing for children (always check age suitability).

Once your child has watched a few Newsround reports and read a few interesting articles they might get the bug for reporting themselves. You can encourage them to write short news reports about things that interest them.

All of these writing activities can be boosted and supported by use of the Atom Learning platform which helps children to secure core English skills in a fun and interactive way.

Actively memorise spellings

Your child’s teacher may be proactive with giving spelling lists, spelling tests and spelling homework. If they aren’t, ask for lists of age-appropriate spellings which you can work on with your child at home.

For each new spelling, help your child to look the word up in the dictionary and ask them to put it into a sentence so you can check they know the meaning.

Stick post-its on your child’s bedroom wall for them to recap before bed. Buy some letter shapes or letter magnets so they can practice the spellings without always having to write them down.

Classroom adaptations

Once you've spoken to your child’s teacher and/or SENCO, the types of support available at school will depend on the types of difficulty your child has, the type of school they attend, the styles of teaching and the staff structures. The class teacher(s) and SENCO should always discuss with you what they plan to put in place for your child.

Simple adaptations should be made in all classrooms as best practice to support all learners. Here are some examples:

- PowerPoints should have a pastel background, sans-serif fonts and navy text. Children can find it hard to read black words on a white background.

- Instructions should be both delivered verbally and written down (either on the board or on a worksheet), even if that is in one-word bullet points.

- Key words for each lesson or topic should be pointed out and briefly discussed to make sure all children have the correct terminology to access the learning.

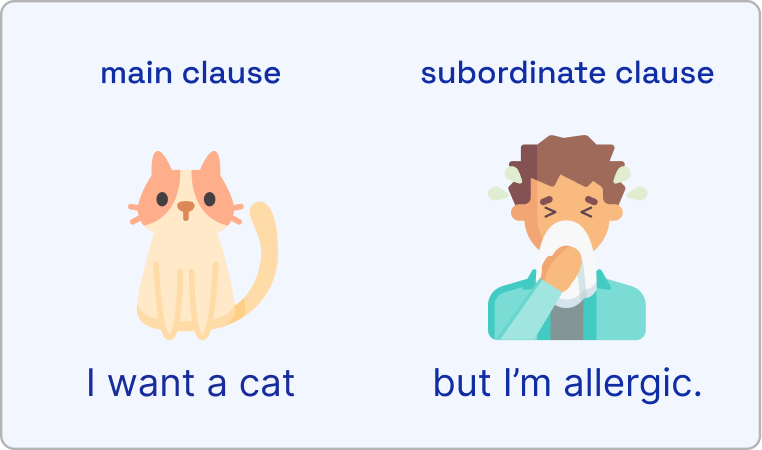

- All new concepts should be dual-coded where possible, i.e. should use both words and images to help embed meaning.

Atom's online learning platform uses dual coding, making it a wonderful tool for dyslexic learners.

And here are some examples of in-class support that may be put in place for your child upon request:

- Sitting closer to the board.

- Using coloured overlays or reading rulers.

- Printing out longer text, so that the child doesn't need to copy from the board but can instead use a highlighter to actively read the text.

- Breaking down instructions and texts into smaller chunks.

- Asking the child to repeat the instructions back verbally before starting a task.

- The child using a mini whiteboard to check difficult spellings with an adult before writing them down.

Diagnosis and specialist support

If you and your child’s school agree there is a difficulty inhibiting their progress in literacy, you may be wondering if you should seek a formal diagnosis. This decision is one only you as parents can make, but one that you should carefully think about.

What does a diagnosis of dyslexia involve?

A full diagnosis of dyslexia is usually done by an educational psychologist and involves a variety of standardised assessments plus observations and discussions with the child, parents and school.

As mentioned in the first Dyslexia Deciphered article, dyslexia is actually defined as a persistent difficulty which does not go away over time despite intervention. As such, an educational psychologist should not be able to give your child a diagnosis of dyslexia after meeting and assessing them at one stage in their life. For a meaningful diagnosis of dyslexia, a child should be observed and assessed at least twice with a substantial amount of time between.

Costs and the diagnosis industry

Over the past few decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of private companies and professionals offering a dyslexia diagnosis service. The diagnoses can be extremely costly and often do not assess the child’s progress over time. As such, many educational psychologists and specialist assessors who work in schools and in local government now refuse to diagnose dyslexia as a snapshot in time and will only consider diagnosis over many years.

So, should we seek a diagnosis?

Here are some key points to consider when making the decision on whether to seek an official diagnosis for your child.

Extra support at home and school

As discussed in our previous Dyslexia Deciphered article, children’s progress in literacy is hardly ever linear. The skills needed to read and write fluently are complex and understandably take a long time to master.

It's important to note that the SENCO will organise support for any child who is experiencing difficulties with learning, whether they have a diagnosis or not.

So now that you've put some strategies in place at home and enlisted the help of the class teacher and SENCO, you may want to wait and see whether they begin to make more steady progress.

Lower stakes assessments

As we've seen, a full diagnosis of dyslexia involves many assessments, observations and conversations and should happen over many years. But there are several simpler assessments which can give you and your child's teachers helpful insights into why they're struggling.

Some examples that can be administered by a Specialist Assessor:

- A TOWRE assessment (Test of Word Reading Efficiency)

- A CTOPP assessment (Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing)

While they don't constitute a diagnosis, these shorter assessments can pinpoint areas of difficulty and help your child's SENCO decide what support might work best.

Self-esteem and wellbeing

Many children are sensitive about difficulties with learning. If you seek a formal diagnosis of a learning difficulty, you should plan carefully whether you want to be explicit with your child about what they are being assessed for and why, and whether you will share with them the diagnosis if they do get one.

A formal diagnosis can be empowering. Many children will be relieved to learn that they have a neurodiversity which causes learning to be different for them. This is especially the case with older children and teenagers.

On the other hand, many learners (often younger children) can experience a big dip in self-esteem if they are diagnosed with a learning difficulty. Some children begin to fall back on their diagnosis when learning becomes challenging. They can see their ‘label’ as a limitation and feel that they cannot achieve as highly as others because of it.

You know your child best of course, and these are things you should think about carefully when considering a diagnosis.

Exam concessions

With school entrance exams or SATs on the horizon, you may feel that your child is at a disadvantage due to the difficulties they are having and they might benefit from exam concessions such as extra time or a reader.

In truth, every child would benefit from having a reader at primary age but not every child benefits from extra time. If your child regularly runs out of time during timed pieces of work it may be that they have slower phonological processing. They need more time than others to complete their thoughts and get them on paper.

If this is the case, your child can access extra time without a formal diagnosis of dyslexia as long as the SENCO has done some assessment of their processing, and has evidence that they often run out of time.

On the other hand, some children with dyslexic-type difficulties do not benefit from extra time. It can lead them to embellish unnecessarily, second-guess their answers and lose the structure of their writing as they try to add more. It's worth thinking carefully about whether exam concessions are the right choice for your child.

Specialist support

Children who have very persistent difficulties learning to read and write can benefit from specialist support from trained professionals, such as Specialist Teachers for Specific Learning Difficulties, or Speech and Language Therapists. Your child’s school may have access to these professionals whose time they can buy in, or you may wish to seek this specialist intervention privately.

These more intensive interventions can be extremely beneficial to children with substantial difficulties. Again, though, there is no need to have a formal dyslexia diagnosis before you access this help. These professionals look at the individual, specific needs of the learner to plan their support, rather than looking at a diagnosis.

University

The only time in your child’s education journey where support will rely on them having a formal diagnosis is if and when they go to university. When applying to university, if your child wishes to access Disability Living Allowance (which includes learning difficulties) they'll need to provide a full diagnostic report of their difficulties written by an Educational Psychologist or Specialist Assessor.

For most Atom parents this is a long way off! But it can still be a factor to consider when deciding whether to seek a formal diagnosis of dyslexia.

The next article in this series will look at exam concessions. Zara will explain the different types of support available for children taking exams and what to consider when getting concessions put in place for your child.

Interested in how technology can help children with special educational needs and disabilities? Learn more here.

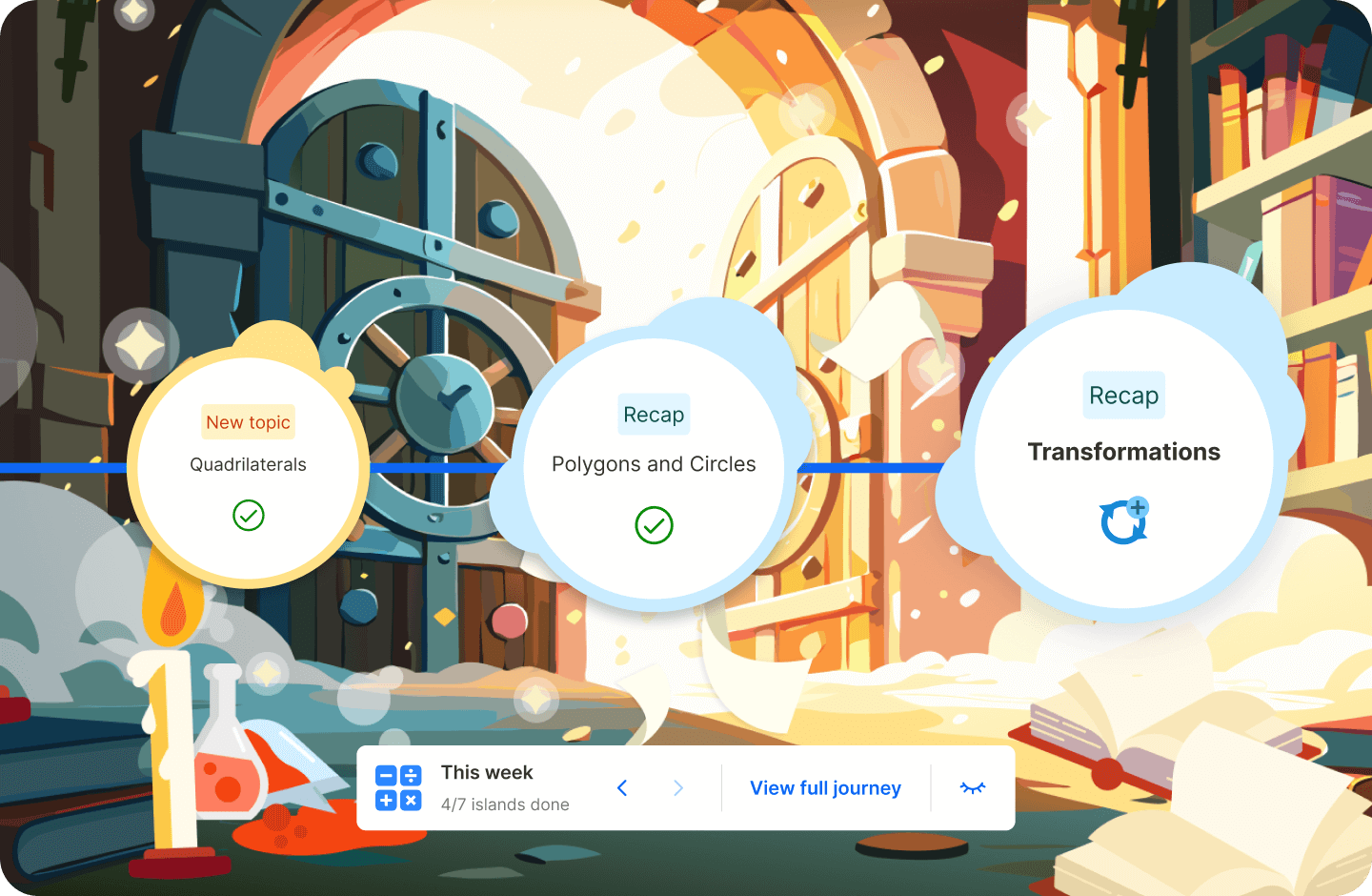

Build strong English, maths and science skills.

Want to support what your child is learning at school, or help them stretch beyond it? Atom gives them the right blend of challenge and support. Help them strengthen foundations, deepen understanding, and grow confident in the subjects that matter most for Key Stage 2 and beyond.

- Follow personalised weekly learning plans that adapt to your child’s level and keep them progressing in English, maths and science.

- Learn through interactive lessons that stretch their thinking and reinforce key skills.

- Track progress topic by topic. See their strengths and pinpoint where they need to improve.

Start your free trial and help your child make real school progress today.